Lately in the field of economics there is a lot of talk about green growth versus degrowth and the incompatibility of our current form of capitalism with the sustainable human habitation of planet Earth.

This online publication is a contribution to that conversation. It is a collection of essays on political economy and the relationship between human systems of survival and the survival of natural systems. While it is focused on the U.S. economy, the ideas can be applied to any nation, and the success of such an economic transformation will be far greater if applied globally.

We have the ability to design a better future. One potential future is a world of equitably shared prosperity in harmony with natural systems and enabled by access to an abundance of clean energy and circular modes of production. How do we get from here to there and rapidly overcome the structural barriers to change?

The philosophical underpinnings of these writings is that of consequentialism. It holds that what makes a decision good is the consequences that flow from that decision. As applied to the design of human systems of economy, politics, and infrastructures, this means that we should create policies and institutions with incentive structures that naturally lead to the greatest outcomes, that maximize the number of people whose lives are defined by happiness and wellbeing.

This is very much in keeping with the philosophy of the founders of the United States of America and the writers of the preamble to the U.S. Constitution. What follows is a roadmap for how to go from a culture of pollution and exploitation (of nature and people) to a culture of regeneration and stewardship (of nature and people), a shift towards a political economy that mimics the stocks and flows of energy and the circular flows of materials that operate (that have evolved) within thriving natural systems. Drawing from thought traditions of both the left and the right, the proposals within these essays should appeal to everyone no matter where they are situated on the political spectrum.

In 1742, coal mining yielded its first five million tons worldwide. The steam engine was perfected by James Watt seventeen years later in 1759. That very same year Adam Smith published his “Theory of Moral Sentiments,” the work upon which the capitalist understanding was established that individual self-interest as aggregated through the activity of free markets can be a powerful force for social progress. There is certainly some truth to the fact that markets can be a powerful force for good in the world. But, as we have seen time and time again, they can also do great harm if there are not sufficient checks on the behavior of corporations or limits placed on the powerful.

Early industrial capitalism thrived on three important feedstocks: 1) colonialism, which supplied land and raw materials; 2) chattel slavery and coercive labor, which kept profits high and centralized; and 3) access to energy-dense fossil fuel energy resources (first coal, then oil). The “capital” in capitalism is deeply rooted in these unsustainably and unjustly obtained resources that were extracted from the commonwealth of nature and society, and which should rather be the equal inheritance of all living things. Instead, this capital was extracted, hoarded, and the profits accrued to private interests holding positions of power. As a consequence of these system dynamics the political economy that emerged to support the industrial age naturally incentivized principles of consumption, greed, exploitation of labor, and the combustion of non-renewable carbon-based fuels.

This is not to pass unnecessary judgement upon the founders of classical capitalist economic theory and the industrialists who worked tirelessly within that system to amass wealth and power. For their part they believed they were doing God’s work. In many ways the cycles of economic growth they powered served to lift millions out of abject poverty and raise the overall standard of living. When its worst excesses were tempered by the progressive era politics of the early 20th century and the New Deal politics of the 1930s the economic engine they built ushered in a century of incredible scientific and social progress. Since then, we have been in a tug of war between those who value unleashing the power of the market and those who feel it requires more constraints. But this game is too simplistic because it accepts the original precepts of the eighteenth-century founding principles as a point of departure. In fact, with what we have learned from advances in science and humanities in the intervening 300 years points to a solution that requires a more holistic redesign of the system.

As a consequence of the era in which is was founded, our current economic system is colonial, dominionist, exploitative, and entirely dependent on the externalization of the environmental and social costs of fossil carbon combustion and industrial pollution. This is not a value judgement, but rather a simple statement of fact. To every season there is a political economy. The problem today is that we have advanced into a new cultural reality and our economics has not changed sufficiently to reflect that fact.

A quarter of a millennium later, it’s time for a new political economy for an era of environmental stewardship and economic democracy.

If we were tasked with designing an economic system to fulfill the underlying promises of the American experiment in liberty and justice? What would that look like?

A new economic system for the 21st century will make the American dream a reality for every person, while maintaining the beneficial features of our current economy that reward industriousness, innovation, and entrepreneurship. We play lip service to meritocracy, but our current system closes the door on it for most people.

This new economic system will bring true egalitarian democracy by laying the foundation for a new paradigm of social wealth that can lead to the carbon drawdown the environmental movement is seeking, while also increasing the standard of living and the free time for all people to enjoy their one precious lifetime on this beautiful spaceship Earth.

The contemporary political discourse is desperately seeking an economic blueprint—a design for a peaceful and orderly transition from where we are now (winner-take-all corporate capitalism) to a socially just and environmentally sustainable economic model that is highly desirable to the general public.

To succeed politically, this new economy cannot be about asceticism or sacrifice. In fact, this new economy should be designed to bring riches to a vast number of people who could never dream of such abundance within our current system of capitalism, which itself is riddled throughout with artificial scarcity, nepotism, happenstance of birth, racism, and class tribalism that limit the opportunities available to Black, Indigenous, People of Color, and those born into poverty to participate in wealth-building endeavors.

There are many proposals out there to reign in corporate power and regulate winner-take-all capitalism. But there are limitations to the efficacy of policy reforms that are a patchwork of repairs layered over our current socioeconomic system that at it core relies on endless raw resources, a linear economy, and a large class of extremely poor and disenfranchised (essential workers) who can be called upon to provide inexpensive labor.

What is needed is a new political economy that removes the countless daily discretionary opportunities for the implicit bias of individuals to create accumulating structural inequity. A system that limits the power of luck and birth fortune and instead rewards merit. We need a new political economy that incentivizes human behavior towards acts that will help to heal a dying planet and regenerate natural systems.

We must take a new look at how wealth is created at the most basic level, and how it can be equitably shared, by design.

The term “greatest economy” can be read in two ways.

In one sense it means an economic powerhouse that increases quality of life and expands opportunities for everyone, while generating wealth and reinvesting in the future. In the second sense it means the most frugal, the most efficient—that which fulfills our needs while expending the smallest amount of resources and energy.

These two readings of the term “greatest economy” may on the surface seem to be in contrast, yet they are fundamentally intertwined within in a closed system like the planet Earth. They are the yin and the yang that give rise to a path of regeneration.

One of the fundamental contentions of my argument in these writings is that our economy functions better for everyone, even the most well-off, when it is just and equitable by design. By designing our social contract to be just and equitable, we will make our society and our politics more democratic and more productive.

According to Ganesh Sitaraman, Theodore Roosevelt wrote that “there can be no real political democracy without something approaching an economic democracy.”

Economic democracy can be defined as relative economic equity. It can be recognized by a low gini coefficient, a measure that reflects the disparity of income within a society.

A Gini coefficient of zero expresses perfect equality, where all values are the same (for example, where everyone has the same income). A Gini coefficient of one (or 100%) expresses maximal inequality among values (e.g., one person has all the income and all others have none).

http://www.fao.org/docs/up/easypol/329/gini_index_040en.pdf

While a 100% equal society is not necessarily the best goal, a gini coefficient of 20% would mean that even the poorest in society can thrive. We were on our way there in the 1960s, as the New Deal and Great Society helped to create a more level playing field for all Americans. But then things changed. Since 1979, the gini coefficient of the United States has risen from 34% to 42%. We have gotten 24% more unequal under a system of neoliberal capitalism. The District of Columbia is 54%. The states of New York and Louisiana are are 52% and 49% respectively. Those with capital and access to capital have built more wealth and have not been taxed on it. Those with debt are taking on more debt and being taxed at higher rates. We’ve not constrained, nor have we balanced our greed. Instead, we have rigged the system for the greedy.

The kind of resource hoarding that we have designed into our current economic system of winner-take-all capitalism is anathema to any system that can perpetuate in the natural world without collapsing. At some point every logistic curve meets its constraint. The parasite cannot continue to grow exponentially within its host.

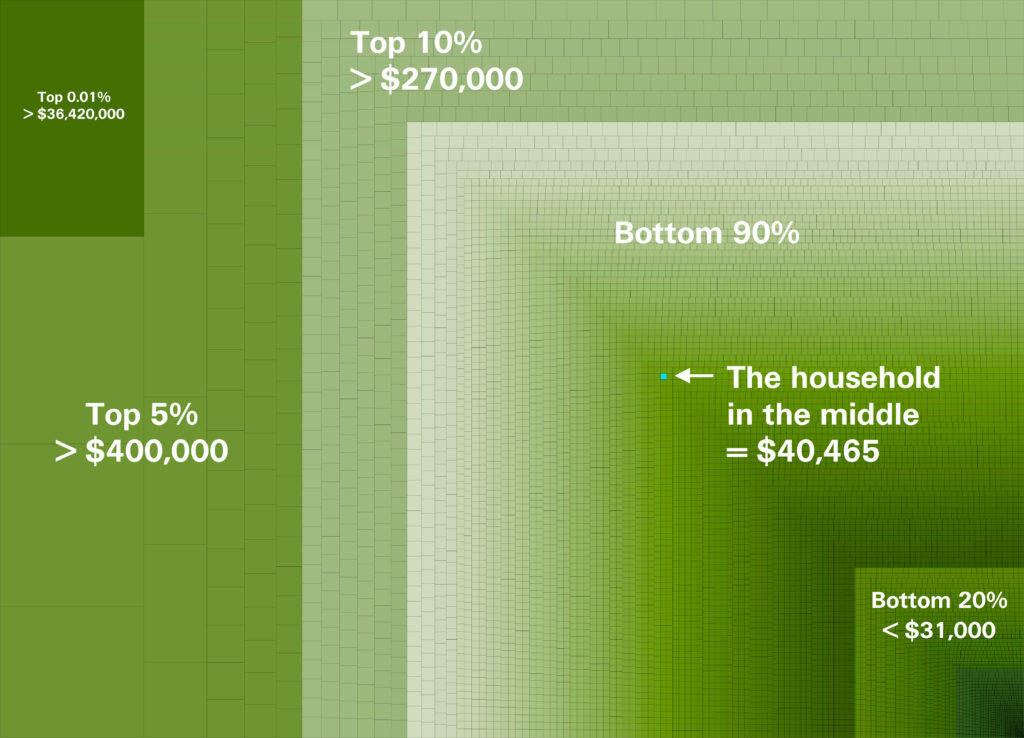

In the image above, the rectangular areas correspond to the total after-tax income of equal groupings of American households.

The large rectangle at the top left is the average after-tax annual income of the wealthiest 11,600 households (some households in the top of that group keep more than $100 million each year, but the average is $36.4 million). Keep in mind that this represents income only. As the 2021 piece in ProPublica makes abundantly clear, the wealthiest Americans do not even take income as a way to avoid taxes. On the lower right where the image gets denser are the after-tax incomes of the majority of Americans.

There are 32,800 people (2.83 persons per household) in every one of the rectangles, even the ones so tiny you can’t see them. If you look closely, you will see a cyan square. That square is the absolute middle grouping of 11,600 households (there are the same number of households above and below). That cyan square represents the 11,600 households that live on $40,465 after federal taxes each year. Households to the right and below that tiny cyan square makes less than that. They are the lower half.

The households to the left and above that small square make above average income. Within that upper half of the population, 7.4% of households reported their self-identified race as Black to the United States census. If income distribution were colorblind in practice, then 13.4% of upper half households would be Black because that is the percentage of the overall population. Instead, in the upper half of the socioeconomic ladder there are half as many black households as we would expect within a colorblind society. The same disparity can be seen in Hispanic, Latinx, and Native American populations. When you look at the households at the top 5% of incomes (those making more than $400,000) the disparities are even greater with only 4% self-identifying as Black. I point this out only to say that it is possible to do better. I’m not implying that any of this has to do with the fault of any one person or any conspiracy by any group of people. I’m not casting blame. Structural inequities are just that: structural. We can decide to change our structures once we are aware of their failings. These structural failings serve as an impenetrable moat around a castle of power. It doesn’t matter who that power belongs to. The problem is the moat, not who it protects.

There are a lot of poor people in the richest country on earth.

There is a dark blue overlay in the bottom right corner. That’s the 38.1 million people who live in poverty. For most of them every day is a struggle to survive. 12 million are children. More than half a million people will sleep on the street tonight.

It’s not necessary. There is plenty of wealth to go around in America.

When you look at the image above, imagine that the tiny squares you can’t even see they are so small in the bottom right corner—those squares are each just large enough for a person to stand shoulder to shoulder with her neighbor. When you get to the top left rectangle, each person is standing more than two football fields apart. They would feel completely alone. They couldn’t see the next person without binoculars. This is America in a way that we rarely get to see it (we’ve designed poverty to be hidden).

This radical inequality is the root of so many of our problems, including partisanship, crime, incarceration, homelessness, entrenched racism, antisemitism, and xenophobia (looking for others to blame for your misfortune), poor health, substance abuse, poor quality education, and the politicization of issues like public health.

In her book, Doughnut Economics, Kate Raworth runs through the research that verifies that more unequal nations, “tend to have more teenage pregnancy, mental illness, drug abuse, obesity, prisoners, school dropouts, and community breakdown, along with lower life expectancy, lower status for women and lower levels of trust.”

This makes sense because all those social ills could be mitigated through investment in education, healthcare, treatment centers, community projects, infrastructure, and social programs that rely on public spending by government agencies. The hoarding of wealth by the top 1% of income earners limits our ability to fund such programs.

Inequality also impacts democratic elections (when money is considered speech under the constitution), hinders our ability to act collectively to address environmental issues, and promotes conspicuous consumption. By separating classes of our society to such polar extremes, political divisions also become magnified. When access to capital is equated with free speech, then a kind of absolute power will inevitably corrupt the system, leading to kleptocracy and oligarchy.

The above image is a tree-diagram of after-tax income over one year. It does not address wealth, which is accumulated income year after year. The households who are in the top groupings in the upper left of the image were most likely born there and will most likely die there. They get to keep piling on year after year and using more and more of their growing capital to accumulate more capital, while those at the bottom struggle every day to get out of debt. There is not much mobility across this chart. A similar diagram of wealth (the link does not break down the top 1% into finer detail) is even more skewed and it would need to show the negative wealth (the absolute debt burden) of the lower 10%.

If we all took a vote, would the households taking home $41,000 or less every year (the majority of Americans) be in favor of designing a more equitable economic system?

The bottom half of our nation’s income earners includes Americans we have come to call “essential workers” during the coronavirus pandemic—the farmworkers, meatpackers, medical workers, sanitation workers, retail workers, first responders, postal workers, and bus drivers. According to the Federal Reserve, “Among people who were working in February [2020], almost 40 percent of those in households making less than $40,000 a year had lost a job in March.” Can we instead design a socioeconomic system that provides a sense of security and a living wage to these foundational members of our society?

Half of the population experiences almost daily stress related to money and basic survival.

The intergenerational trauma brought on by unnecessary poverty and extreme inequality has negative impacts on all tiers of society, entrenches class immobility, and reinforces what Isabel Wilkerson calls a modern caste system. Studies of inequality in educational outcomes have pointed to early childhood education as a defining factor. Children whose parents struggle to make ends meet do not have access to the kind of pre-kindergarten learning experiences of children from more affluent households. Those who are fortunate enough to live in the top 10% are mostly able to live lives secluded from reminders of poverty. They are able to provide opportunity and education to their children. But the global coronavirus pandemic has shattered this illusion of insulation. We can see now how interdependent we all are upon one another.

A part of the design of our present socioeconomic system is inherited from earlier systems. It is born of a fetishism of the aristocratic class, and the normalization of nepotism and cronyism in life and politics that is related to it. In the modern era this design feature has invaded the zeitgeist of nearly all political commentary with a media class and political class ensconced within a top 1% information echo chamber with a megaphone of unprecedented proportion.

The divide between class perceptions has fueled conspiracy theories and allowed demagoguing politicians to create expanding layers of rhetorical wedges between people, dividing and conquering, redirecting blame for personal misfortunes brought on by the structural failings of capitalism onto traditional scapegoats: BIPOC and immigrants.

The divide between class perceptions leads to the use of words like “criminal” and “inmate” to dehumanize people of lower classes who are in many cases themselves victims of our present system of injustice that locks people away for nonviolent infractions and deports people for minor drug possession—people with families who then suffer generational trauma—while failing to hold criminals of higher class accountable when they commit fraud, wage theft, bribery, or other crimes with far more serious social victims.

“Crime is a problem of a diseased society, which neglects its marginalized people. Policing is not the solution to crime.”

Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez

The above words ring true to many of us. We feel deep down that if only we could remove the social conditions that give rise to acts of desperation and avarice, we could do a far more efficient job of reducing crime rates than is possible through further expansion of the police state. At some point there is a limit to the draconian military tactics that law enforcement can take to stem the social unrest that results from massive income and wealth inequality. We may be running up against that limit today in America.

Design can change the world.

It can also rig the system.

There is not much that we’ve left to chance over the years. We’ve designed it all. Those making design decisions, however, have not always had at heart the interests of the working class or of mother nature. More often than not they were redesigning one small part of an overly complex system already full of loopholes. In other words, the “alignment problem” that we hear about so much in the context of AI is not something new. Policy is algorithm and the alignment problem dates back to the drafting of the U.S. Constitution.

The design of our socioeconomic systems over time has intentionally rigged our economy to siphon income up to those who already hold the vast majority of the nation’s wealth. Many economists such as Thomas Piketty make the convincing case through data that ever-expanding inequality is a fundamental design feature of capitalism—a feature that must be transcended through progressive taxation, public investment, pro-labor policy, and regulation. He writes that “extremely high levels” of wealth inequality are “incompatible with the meritocratic values and principles of social justice fundamental to modern democratic societies.”

Our present system has also been designed to exploit nature as a resource to the point where we will soon witness major ecosystem collapse and the most dire effects of climate change if we maintain our rate of increase of consumption and pollution. It has led us to the point where we have locked in 1.5 degrees Celsius of global warming even if we stopped burning fossil fuels this decade.

This site is a collection of thoughts on inequality and the incompatibility between modern capitalism and environmental sustainability, with some sketches of potential solutions.

In thinking through new systems, I try to maintain the best parts of capitalism and leverage the power of the marketplace of goods, services, and ideas, while eradicating poverty and all of its adjacent social problems.

In these writings you’ll get to see what your after-tax income would be under two new systems of taxation. You’ll learn about a new system of wealth creation, terrametrism, that can replace the one we currently have. The new system replaces the broken foundation of capitalism with a revaluation of value to align social wealth of human economies with our sustainable stewardship of the planet.

It’s my hope that my ideas will find resonance across the political divide. They are non-partisan. Still, I have no illusion that Congress would enact a new terrametric monetary standard anytime soon. These are most likely policy proposals for a decade or more in the future. I also know there are many other great ideas out there, like carbon coins and progressively taxing carbon while maintaining more of the status quo. I’m in favor of pursuing all of these options as long as they can get us to an equitable future in harmony with nature.

Robert Ferry is a LEED accredited architect and the co-founder with Elizabeth Monoian of the Land Art Generator Initiative, a non-profit that is inspiring the world about the beauty and greatness of a post-carbon tomorrow.